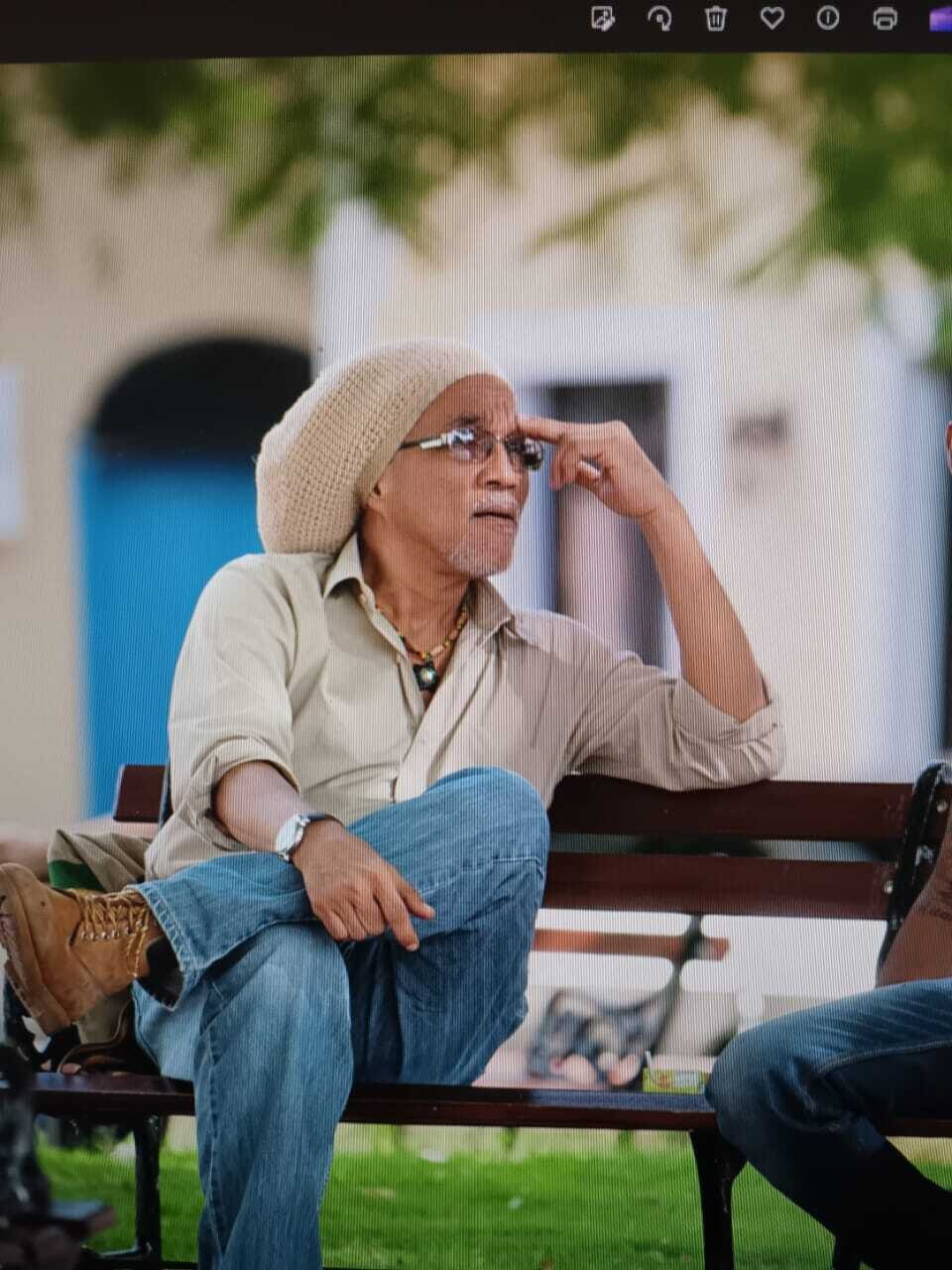

For months, years… and for some, almost a decade. Social researcher Gilberto Toro was there. It ended when Panama decided to no longer speak of it. Not as an official. Then the Red Cross arrived. The food was military: plastic bags, cookies, chocolate, canned cheese. At first, it was a novelty. He was handcuffed. By dawn, he was displaced. The bombs stopped falling, but El Chorrillo had nowhere to return to. Overcrowding. Not for weeks. The Americans left. The camp collapsed. No one wanted it. The open wound. Thirty-six years later, Toro is clear: the invasion did not end when the shooting stopped. Not as a visitor. The neighborhood returned… different. The compensation failed because the real magnitude of the damage was never understood. No one calculated that. Collapsed bathrooms. And in those days, mere resemblance was enough. The interrogations were mechanical and cold: American soldiers with covered names, dark sunglasses, repeated questions regardless of the answer. They believed Toro resembled an explosives expert. Others invaded unfinished buildings because they could no longer stand it under the hangar. The Red Cross could not cope. Official records preferred to count the dead and aid, not the true scale of displacement. They speak of up to 20,000 displaced people, mostly from El Chorrillo, scattered among churches, schools, and makeshift camps. Entire families organized, walked together, returned with bags of food. It was during this return that the Hummers appeared, the shout of 'Halt!', the dry fear. A trophy. He was barely in his second year of college, short hair, an athletic body. That is why today there are buildings without functional elevators and generations that learned to go up and down the stairs of life. Many did not return. To endure. The incomplete return. The State's original plan was not to restore El Chorrillo. The cash registers, yes. What followed was not reconstruction: it was an internal exodus, silent, managed with imprecise numbers, military rations, and a brutal urgency to turn the page without reading it. One of the points where this wound was concentrated was the Albrook hangar, in what was then still the Canal Zone. A space designed for airplanes ended up converted into human shelter. It was not just 'the people'. All social classes looted. To make a new one. First, you had to eat. But there was no time. Not for days. The old buildings, they said, would not be used again. But the decision was different: to restore, patch, and support with wire. And even so, it stretched as far as it could. Insufficient water. Then came the punishment. Eating the same thing for weeks turns any aid into an elegant form of exhaustion. A hangar full of families cannot last six months without breaking. The government took control. As part of the neighborhood that survived the destruction and was relocated under a metal roof where El Chorrillo continued to exist, compressed, watched, and exhausted. The crossing. Toro remembers the crossing to Diablo, where there was still a stocked store. It looked like a Defense Force. No resources. American paramedics could not communicate with the people of El Chorrillo. Language was another form of abandonment. And that selective silence is also part of the trauma. The Albrook hangar no longer houses families and doesn't even exist, but in the minds of those who were there, it still houses an uncomfortable truth: Panama preferred to close its eyes rather than close the wound. And a country that lives like this does not overcome its history. It drags it along. The entry. Under the Albrook hangar: the city that Panama decided not to remember was first published in La Verdad Panamá. The plan was to demolish it. Desperation. Everything that happens in a neighborhood happened there, but without doors to close or corners to hide in. The language of pain. Toro went from being detained to being an interpreter. There were the children who needed urgent psychological attention. Some took hams. Others took televisions, cars, thousands of dollars. Libraries were of no interest. He walked from tent to tent, carrying their pains, explaining medications, calming their fears. Thanks to that, medical care began to flow, but not the trauma. When they were given paper and colored pencils to the children, they did not draw new houses. They drew helicopters shooting, corpses in the street, buildings on fire. It was a collective diagnosis. The comfortable version says that 'the people looted'. The reality is less simple and more uncomfortable: not everyone went out to rob, many went out to buy so as not to starve. And that silence explains too much. The normalization of violence. The 'live for the moment' as an unwritten law. Gangs as an unattended legacy. Displacement turned into a real estate opportunity. Even the looting was told half-truths. Toro offered to translate. They were not families of four. When the invasion of December 20, 1989, ended, Panama did not wake up in peace. Detained. Albrook was the largest of all: a provisional city without privacy or a horizon. There were former soldiers, civilians, the elderly, pregnant women, children who had seen too much. Others returned partially. Until the yellow ticket arrived, a strange permit that did not mean freedom, only transit. The hangar. The Balboa High School and then the Albrook hangar were filled with thousands of people. There was no clear census. Afterward, it became routine. Extended families: grandparents, uncles, grandchildren, all clinging not to separate because to separate was to disappear. Security was in the hands of the US Military Police. Abuse. No state interest. They were families of eight, ten, twelve. Photographed. Some accepted relocations to the East or West. It was not convenient. To sleep. Fights. They would not let them go that easily.