For the First Time in 40 Years, Panama’s Deep Waters Did Not Rise and the Ocean System May Be Collapsing

This incident, described by the Smithsonian Institute, raises questions about the climate vulnerability of tropical ocean systems, where even relatively small atmospheric shifts can result in substantial ecological impacts.

"If we hadn't been there with a ship at the right time," said co-author Hanno A. Slagter, "the whole event might have slipped under the radar." This statement, included in the full research release, points to an ongoing need for better data infrastructure in the tropics.

The study outlines two broad scenarios: one in which the anomaly reflects natural variability, potentially linked to multi-year patterns such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, and another in which anthropogenic climate change is modifying the tropical wind systems that sustain upwelling events.

At the center of the disruption was a collapse in atmospheric drivers. The northern trade winds, normally responsible for triggering the upwelling process, were significantly weaker in early 2025. As a result, surface waters remained in place, and the temperature differential needed to initiate vertical mixing did not materialize. Satellite observations confirmed reduced chlorophyll-a concentrations throughout the Gulf of Panama during the period when biological productivity typically peaks.

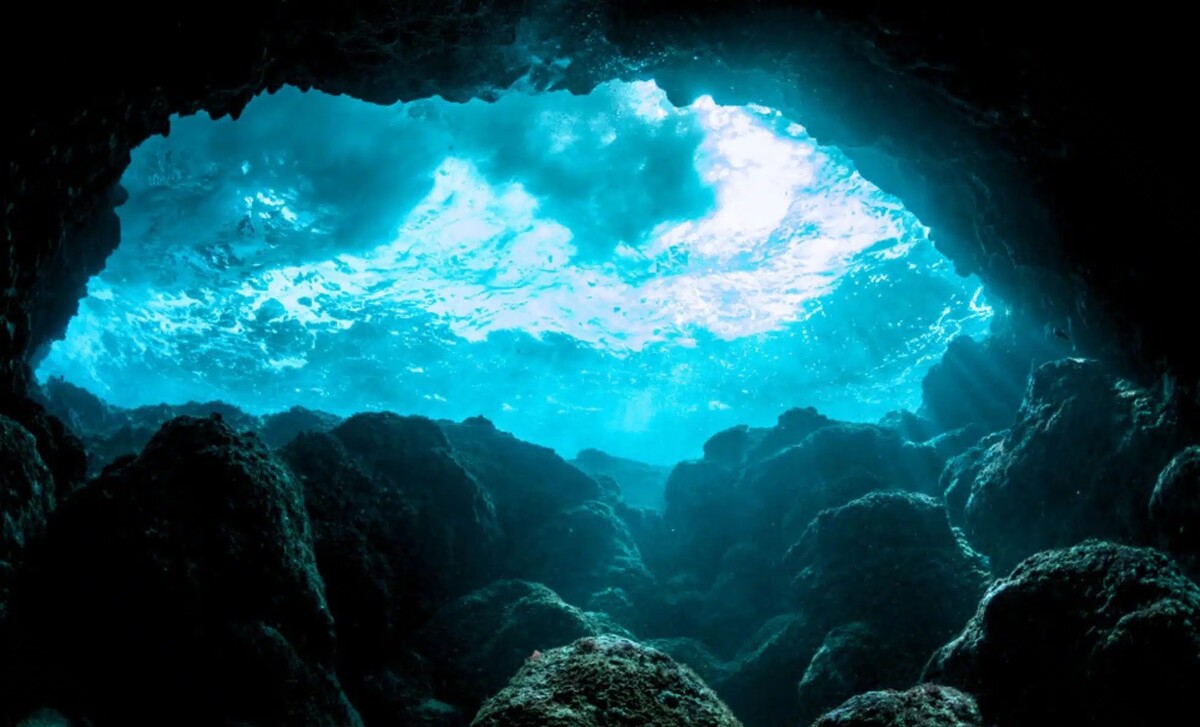

A visual analysis shared by the research team showed marked differences in ocean productivity compared to previous years. The imagery, based on chlorophyll concentrations, illustrated how the biological engine that normally activates during the dry season never switched on.

This reduction affected key fish species, including sardines, mackerel, and squid, which support both artisanal and commercial fisheries. Although full economic impacts are still being assessed, preliminary data point to declining catch volumes in multiple coastal communities.

Coral reefs in the region also faced increased thermal stress. Without the usual cooling influence of upwelling, conditions favored coral bleaching, which researchers note may become more frequent under warming scenarios, as highlighted in STRI's official announcement.

Researchers noted that this shift eliminated a key stabilizing mechanism in the region's marine ecosystem and exposed vulnerabilities in the broader ocean-climate system. Atmospheric models used in the research indicate a correlation between weaker winds and altered pressure patterns over the eastern Pacific. However, the authors stop short of attributing the breakdown to a single cause.

The findings raise questions not just about local dynamics, but about broader changes in tropical ocean systems that have remained under-monitored and poorly understood.

Whether the 2025 disruption represents a one-time breakdown or an early signal of systemic change remains unresolved. Without baseline data and real-time observations, researchers say, it will remain difficult to detect early warnings or understand the thresholds at which long-standing oceanic processes begin to fail.